The Master Project is a new curriculum initiative at the Royal Conservatoire in The Hague that aims to create a holistic and student-centered learning environment through a profound integration of artistic development with research and professional integration activities.

An empowering new curriculum

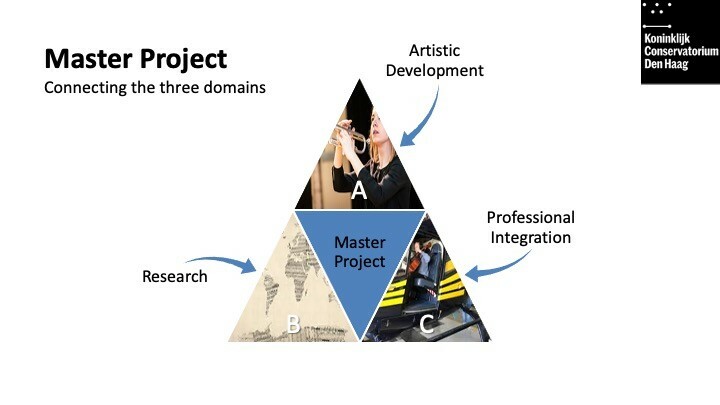

The Master Project (MP) has a tripartite structure that combines the following three activities in one large project designed by the student:

- the artistic development of the student (AD)

- research (RE)

- professional integration activities (PIA)

– Feedback from former students describing how they left the Royal Conservatoire unprepared for the realities of their profession has made us attentive to the gap between musical education and professional life, says vice-principal Martin Prchal.

The Master Project draws on aspects of the European Master of Music for New Audiences and Innovative Practice (NAIP) and on the Conservatoire’s long-standing expertise with artistic research at master’s level. Our experience with NAIP has shown us that students learn best when they are given the opportunity to create activities themselves that are close to their own artistic and intellectual ambitions. Artistic research, on the other hand, provides consistency to artistic experiences, helping students to develop their personal interests and artistic identity. In this new context, artistic research works as a steady glue between artistic practice and professional work by articulating processes and methods that can potentially evolve into new musical practices. Combining reflection and entrepreneurship in the new curriculum, we hope to better prepare musicians to express their own artistic voices in an increasingly complex professional landscape.

The programme is applicable to a range of disciplines including Early Music, Art of Sound, Classical Music, Jazz, Vocal Studies, Conducting, Chamber Music and the NAIP-programme. The Master Project was initiated in the academic year 2019-20, and the first group of students admitted to the new curriculum completed their degree in 2021. This article builds on descriptions of the programme, experiences from staff and leaders and from interviews with master students on their experiences.

The innovative aspect of the Master Project is to introduce a professionalising component that would reflect the artistic and research goals of the student. As such, the PIA may represent a space in which to present research findings or a context in which to carry out research. By way of illustration, a student concerned with audience experience used her research component to explore the traditions and conventions of musical performance practice, and her PIA to experiment with them within self-designed performances. Through these interconnections, the PIA gains in depth, research becomes alive, and the motivation of the student increases.

[Students] are constantly encouraged to make their own choices and develop and carry out their ideas and plans. We challenge them to connect all three domains [artistic development – research – professional integration] in a way that is meaningful and relevant to them, so that they can find their ‘niche’ and prepare themselves for a professional practice after they have completed their studies

(Excerpts from the Master of Music Handbook, 2020/2021).

The Master Project proposals submitted by the students so far upon admission to the degree are very diverse, including numerous crossovers between musical genres and other disciplines such as sports, law, healthcare, dance, visual arts, literature, theatre, psychology, culinary, web design, marketing, computing, phonetics, management/team building, theology and geopolitics. Such projects bring new knowledge to music and in many cases also musical knowledge to other domains. One example of the latter is a master student who collaborates with a chef to develop a concert for guitar and candy, drawing on insights from neuroscience and gastronomy to propose new sensorial experiences.

“What I like about the Master project is the possibility of focusing on a segment of my profession and having time to create a complete story around it”

(Natan, Classical Department)

In general, what students like in the Master Project is the freedom to experiment and combine different interests. This freedom challenges commonplace assumptions such the idea that reflection kills the magic of music, that one needs to spend all of one’s time practicing to become a good musician, or that being entrepreneurial means following the marketplace. Time to concentrate on a single topic or aspect of one’s practice is also valued. The most motivated students even report taking up activities outside the conservatoire to complement the MP. Further, students mention the ‘humane’ and entrepreneurial orientation of the curriculum absent from more technically oriented institutes, and a relation with the ‘real world’ which they consider as extremely valuable for a conservatoire. Even more positive is the fact that the students seem to feel supported by the school, even though they are asked to take responsibility for themselves and their studies; as one student says.

In the process of designing and implementing one’s own master project, questions arise, unsettling students and igniting their imagination. Most of the students interviewed agree that the programme widens their horizons and prepares them for the future. This is both in terms of making them consider career paths beyond traditional models (‘to do something different’, as a student puts it), or by realising that musical and/or extra-musical passions and interests can be explored professionally.

Naturally, some students have mixed feelings about the Master Project or need time to adjust. Even so, most of them agree that the process is transformative. For instance, a student describes the curriculum as ‘imposed’ but challenging: ‘it makes me less lazy’, he says; ‘without this push I would probably just practice my instrument’. Another student confides that the problems she experienced while realising her master project, including finding her way across conservatoire departments and hierarchies in the search for partners and resources, made her more aware of her responsibility for her studies and career: ‘It was a frustrating process, I ended up having to do a lot by myself’, she reports, ‘but it was a lesson for life’.

“A big space is given to the students, but then I know that it is my responsibility to fill this space”

(Michelle, Student, Classical Department)

The first generation of Master project-students was hit badly by the pandemic. On top of loneliness, practical problems such as lack of physical access to performance partners, instruments, sources, and the impossibility of organising activities outside the conservatoire, made it difficult for them to stick to their original plans and wishes. The flexibility of the Master Project and the intensive contact with the teaching staff allowed most students to overcome these setbacks in creative ways, confirming the perception of the Master Project as a valuable format to prepare for the challenges of today’s changing professional field. The second generation of Master Project-students starting in September 2020 also suffers the consequences of the pandemic but since most students have thought their projects within a ‘corona framework’ from the start already – planning recordings, working with digital media and so on – they find themselves less vulnerable than their senior peers.

“Emphasis on research and entrepreneurship makes one see differently than one usually does. This is even more important now since the coronavirus”

(Maud, student, Early Music Department)

So far, one of the most stimulating results of the Master Project has been the cooperative atmosphere amongst the students. We learn from the interviews that students seem more concerned with helping each other than with competing against each other. This might have to do with the fact that the programme emphasises students’ differences and complementarity rather than then comparing them. Some students also choose to develop their Master Project together with other students, which is possible if their individual roles and interests are well articulated and possible to assess.

The Conservatoire cultivates this collegial culture by creating occasions such as the StartUp!Week, where students can connect informally, or by organising master circles, where newcomers and second year students mingle and exchange about their individual projects and experience. Finally, we work towards increased student presence and agency in the Conservatoire, for instance as members of our Council of Representatives and in the working group monitoring the development of the new curriculum.

Still, the promising beginnings of the Master Project cannot be explained only by what the Conservatoire ‘did right’. It is working because the Master Project is relevant to a new profile of students with a new mentality, emerging from a changing musical life where personal interests, social engagement, reflection and autonomy weigh more than traditional conformity. In this sense, the Master Project is but adapting to a reality that is already there.

How it works

Curriculum integration in practice

As mentioned earlier, the Master Project combines artistic development (AD), research (RE) and professional integration activities (PIA) within one larger project of the student’s choice. The way these three activities feed each other varies from case to case. For some students, the PIA function as a laboratory for the research. In other projects, the research may feed the PIA or the PIA is used to disseminate findings from the research. Whether PIA and research feed, illustrate or complement each other, what matters is that they are directly connected to the student’s artistic development, that they represent a personal career opportunity, and that the relationship between research, professional and artistic goals is clearly articulated. Examples of such artistic goals and needs have been becoming a more self-confident performer, communicating better with audiences, and expanding the interpretive and technical palette. Below are concrete examples of master projects created by students:

- setting up concerts in different venues to understand how space acoustics impacts on articulation,

- organising workshops with lawyers and sports people to investigate stage fright in performance across disciplines and become a better communicator

- investigating how visually impaired people use digital tools to develop a music production software for the blind.

- designing a method for singing high notes in jazz and research one’s own practice to come up with good exercises and techniques

- preparing a new edition of Mozart’s horn concerti after studying historically informed interpretation research

- exploring theoretically the challenges involved in historical stagings of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo and creating one’s own staging

The programme includes:

- compulsory introduction seminars on research and project management

- elective courses on a variety of subjects

- personal supervision in research

- personal coaching for professional integration

- vocal/instrumental lessons

- chamber music/big band/ orchestra projects

- master circles where students and teachers meet to discuss their projects as they unfold

Students develop their Master Project within and alongside these activities, and in contact with external stakeholders such as concert and conference managers, editors, software developers, recording studios and web designers. Outcomes of the master project include a written reflection as well as artistic and research presentations and/or products shown within or outside the conservatoire.

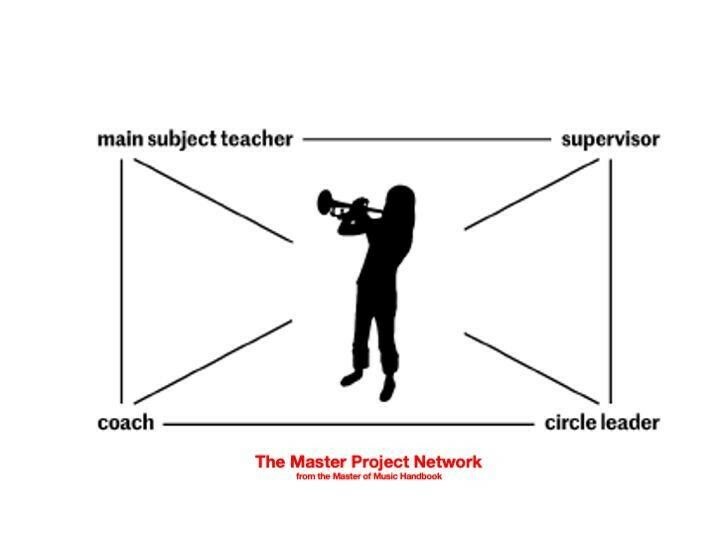

Taking a closer look at the activities and coaching offered by the conservatoire, each student is supported by a so-called Master Project Network (MPN) formed by a main subject teacher, a research supervisor, a PIA-coach and master circle leader. The MPN follows the student from the start of the studies and throughout the whole degree. They are assisted in this by the heads and coordinators of master research and professional development, who are always available to the students for individualised advice.

The main subject teacher holds a central position in the MPN: (s)he is concerned with the instrumental and artistic development of the students, helping identify artistic potential and needs that might be fruitfully explored within their master project. The PIA-coach helps with networking, contacting venues and advising on how to raise funds for the PIA. Ideally, PIA-coaching takes place outside of the safe environment of the conservatoire, including the virtual space. We operate with a pool of external PIA-coaches composed of professionals active in a variety of musical field, matching the area of expertise of the coach to the student’s area of interest; thus, a conducting student working on a partnership between his local music school and wind band will be advised by the outreach specialist of a professional orchestra. Research supervisors are usually teachers of the Conservatoire with special experience in research, Students can receive external research supervision if their areas of interest are not covered by the expertise available in the Conservatoire, as in the case of student researching instruments not taught at the school.

Master Circles are monthly encounters in which students can discuss their master projects. They are structured around nine thematic research areas. As these research areas are generally not tied to specific instruments or disciplines, they bring students from different departments in the circle meetings together. Students choose one of these areas for their entire master project. These master circles have become the place where the three domains of the master project come together, with students holding regular presentations about the content and development of their projects. The circles are led by a master circle leader who facilitates feedback and peer-learning through an open dialogue between students. Where the main subject teacher, PIA- coach and research supervisor all focus on one domain only, the master circle leader will inspire students to actively relate and combine the different aspects of their studies.

In the seminar Introduction to Research in the Arts, students become acquainted with artistic research methods and techniques as well as with teachers and other guest speakers representing the different departments and research strands of the school. In addition, personalised assignments help students formulate their RE topic and questions with an eye for their AD and PIA; these include reflection on the interests and competences of the students, and how rewarding/important a topic may be for the field, for a broader community and for them professionally.

In Introduction to Project Management, students learn basics of management planning such as design thinking, budgeting, creating a portfolio, social communication, regularly meeting external guest speakers who bring them into contact with the professional world beyond the school. Like in the research seminars, students are given individual assignments asking about their motivations, the social relevance of their project and how and where they see themselves in their future as artists and professionals.

After an intensive first semester of introduction seminars, students spend most of their time working on their individual projects, with the exception of traditional activities such as orchestra, chamber music, big band, master classes and other, which come to support their artistic development. Alongside these activities, they can choose between one or more elective subjects from a palette of over forty courses ranging from music theory, education, aesthetics and interpretation to science, philosophy and writing skills. These electives have also been grouped around the focus research areas, including Art of Interpretation, Instruments & Techniques, Music in Public Space, Creative Practice, Beyond Discipline, Musical Training, Performance & Cognition, Aesthetics & Cultural Discourse, Educational Settings and Music Theory & Aural Skills.

The final assessment include a final recital, a research exposition published in the Research Catalogue and presented during an annual Research Symposium, and the documentation of the PIA carried out outside of the four walls of the conservatoire, accompanied by a critical reflection on its conception, implementation and outcome.

While final recital and PIA sometimes coincide, the Conservatoire hopes over time for new and flexible presentation formats that would allow for the three domains to converge even more seamlessly. For now, overall assessment takes into consideration the way in which the three components relate to each other. Assessment criteria are adapted from the AEC’s Polifonia/Dublin Descriptors (2010) and the AEC’s Learning Outcomes for 2nd cycle studies (2017), including among others:

- the ability to formulate questions and articulate the relevance and outcomes of research in relation to practice

- the ability to communicate about own work and/or process

- the level of autonomy and the capacity of studying in a self-directed manner

- awareness for the wider cultural and professional context

- a realistic approach to project-planning realisable within the two years of study

- the ability to integrate AD, RE and PIA in a creative and promising manner.

The impossibility of defining universal sets of criteria to assess all master projects the same way forces us to keep these criteria flexible, and to redefine our expectations each time according to the nature of the proposed master projects. We find it likewise important to listen attentively to the emerging trends among students, adapting the curriculum to it and creating new inspiring examples through teacher/collaborative research. More challenging is the assessment of PIAs carried out outside of the conservatoire when the physical attendance of the teachers is not possible, as in the case of a student planning a concert tour to China (indeed, students planning to go back to their home countries after their studies often decide to realise their PIA abroad, where they already have, or wish to create, a network). Our current solution is to supplement audio and visual documentation with a critical reflection on the process and realisation of the project, thus evaluating what the student has learned from the project as much as the final output itself.

“Coming here you must split your energy into different directions. Confusing, loss of focus. Second year is better. I believe this crisis is good for me. I had concrete plans for the future before starting the school, and wanted to become an orchestra musician; now everything is different; I have opened my mind, thought and seen other stuff”

(Alberto, student, Classical Department)

Challenges and solutions of the new curriculum

How to teach

While the response to the master project is decidedly positive, the process of implementing the new curriculum is still ongoing and not without obstacles. Clearly, the biggest challenge is the paradox of acknowledging the interests of each student while operating within a common curricular framework. How to reconcile a student-centred approach with the institution’s responsibility to offer professional support, guidance and orientation (Craenen, 2020)?

The current solution offered by the master project is to combine highly specialised artistic expertise with more open, cross-disciplinary and collaborative tools such as peer-learning, while also implicitly promoting artistic, academic and ethical values including artistic identity, originality, entrepreneurialism, inquisitiveness, self-reflectivity, rigour, transparency, cultural and social awareness, etc., all of which substantiate learning goals and assessment criteria.

We believe that the positive response to the master project gathered so far is due in great part to individualised student follow-up and teacher training as described above, as well as to an open and resourceful environment where students feel entitled to express doubts and dreams.

Therefore, we constantly work at improving internal channels of communication so that students can more easily forge collaborations across the different departments of the Conservatoire. We also count on our moving to the Amare building in 2022 to further expand our collaborative in-house network. The new structure will house, in addition to the Conservatoire, the Residentie Orchestra, the Zuiderstrand Theatre and the Nederlands Dans Theater. Also, we make use of the expertise and spaces available at partner institutions whenever possible, working constantly to strengthen interinstitutional partnerships. This is for instance done by giving students access to seminars and courses from other Conservatoire departments and institutions such as the Leiden University and the Royal Academy of Art The Hague, or by creating infrastructure for interdisciplinary work across institutions, the most recent example being the new platform for interdisciplinary research collaboration between the Royal Academy of Arts The Hague, the Royal Conservatoire and the Academy for Creative and Performing Arts at the University of Leiden.

On top of strengthening external partnerships, we are constantly working towards improving the infrastructure of the project and multiplying the resources available to the students, for instance, by considering the possibility of extra budget for individual projects, since most PIAs require funding and not all students can apply for public or other local funding, non-Dutch nationals in particular.

Giving the students more responsibility for the concrete choices and contents of their programme implies the engagement of dedicated supporting pedagogical staff, as well as specific staff training. As far as training is concerned, the members of the MPN receive training and advice from the Conservatoire during study days on different approaches to supervision and teaching. They are encouraged to reflect about teaching and research ethics, and to learn about different working forms including mentoring and the use of constructive feedback techniques. Further, the Conservatoire supports teacher and staff research aimed at improving the new curriculum such as the research on self-regulating techniques by Susan William or the ongoing experiments with semi-formal learning ‘Pods’, where students from different departments team up to experiment with different forms of peer learning.

The analysis of the 2020-2021 master project proposals indicates an inspiring influence of teachers who are themselves involved in research and innovative practices. Specific trends in student choices, such as the popularity of research topics related to mental training or cross-disciplinary practices, may partly be a response to the interests and expertise of teachers and supervisors. This also makes us aware that a student-centred curriculum cannot rely solely on the autonomy of the students, but organically creates a two-way dynamic. Students show awareness of the expertise we have available and partly adapt their choices to it.

Determining the extent of the integration between the different components of the curriculum is an important question. Should everything point in the same direction? For instance, should all activities that the students are credited for during their Master trajectory be closely related to their overall artistic, research and professionalising goals? We see in the choice of electives that although most students choose a course that is directly related to their master project, others use the opportunity to cultivate other interests. In what concerns the daily work of the student across the different components of the master project, students adopt different strategies, such as consequent journaling or using the online Artistic Research Catalogue as a database for their recordings and notes. There is still much to do in this respect, though, and as mentioned above, teacher research has an important role to play.

“The MP encourages me to be a more complete artist”

(Aseo, student, Jazz Department)

Currently, the communication between the master project network members is sporadic, and it is up to the student to organise meetings involving more than one of them. This responsibility is essential if the student is to maintain – or to learn to maintain – a certain autonomy and the control for the unfolding of his/her project. The matter elicits contrasting views, with about half of the students interviewed for this article suggesting that supervision would be even better if there were more communication between supervisors, coaches and teachers, and the other half, mostly students with a very clear vision for their project from the start, preferring to keep the separation. To increase the contrast, some students express the wish for only one supervisor/teacher instead of many, whereas others consult with even more teachers than those assigned to them.

Constructive comments by students in this respect include having a contact person that helps students structure the master projects in a more personalised fashion, for instance someone who looks at what the student knows and doesn’t, what skills he or she possesses and that can advise on what other competences the student should acquire, how to work across departments at school or access other competences also present at school. This is a difficult issue that can certainly be taken up again as the new curriculum matures.

With instrumental and vocal lessons often taking place in isolation from other conservatoire activities, it will be important for the success of the new curriculum that the conservatoire involves instrumental and vocal teachers in the planning of the programme and the evaluation of the students, and that they become invested in it. Students seem indeed to take great benefit from the interest and active involvement of their main subject teacher in their master projects. Some students choose not to discuss their master projects with their main subject teacher to keep some independence (in the case of particularly overbearing teachers or teachers with whom they have studied for very long) or to avoid ‘wasting playing time. However, these same students admit actively using the experience of the classes in their research or PIAs without involving the teacher in their processes.

“Teachers are there to help, I can get hold of them if I need support”

(Michele, Classical Department)

The master project is a holistic curriculum, which is to say that the reflective, theoretical, and practical aspects of the curriculum work together to invite students to explore ramifications and possibilities for their practice. Similarly, students are encouraged to take more decisions and initiative than in the traditional top-down master-pupil model. However, this long-established hierarchy, tightly connected to the authoritarian, ‘knows-it-all’ image of the conservatoire, remains ingrained in the minds of students, teachers and staff. Such scepticism, we find, is often connected to the student’s difficulty in defining or articulating his or her own needs. Indeed, performers, and especially those trained within an authoritarian culture, are generally not asked about their artistic visions or motivations. This is certainly true for classically trained musicians, used to thinking in terms of what the music needs, rather than of what they want. How to transform this image into that of a school that learns through the students? Isn’t the old authoritarian mentality lurking behind the apparent openness of the programme? Furthermore, given the choice, in what direction to think: should artistic goals relate to performance practice, f.ex. enhancing one’s expressive palette or diversifying the repertoire? To the student’s wishes for a future career, f.ex. conducting a professional wind band? To musicianship in general, f.ex. becoming more at ease on stage?

One of the ways of dealing with these issues within the master project was to base all assignments of the introduction seminars on research and project management on the student’s master project aiming at a revised master project proposal to be submitted in the beginning of the second semester. Secondly, we have made efforts to improve the communication material on the programme, including web posts and handbooks, but also proposal forms and evaluation criteria, to make sure that the language used is clear and reflective of the openness of the new curriculum. The results of these efforts are apparent when comparing interviews with first- and second-year master students and realising that the second generation of students not only understands better the scope and expectations of the programme than their senior colleagues, but also shows a more positive attitude to the MP. Finally, it was necessary to opt for a radical intervention in the curriculum, involving most staff and teachers and encompassing nearly all aspects of the master’s for the whole length of the programme, rather than sporadic projects. Only then could we address old habits and hierarchical structures in a meaningful and sustainable way.

As a last remark, it is important to remember that the programme is still very fresh and that the observations and strategies above are still preliminary. After the first generation of MP-students graduate in 2021, we will be able to look more closely at how the ideas of the students evolved from the moment they started the programme to the end of their trajectory. We hope that this knowledge might tell us something about the impact of the conservatoire upon their choices and lead to future improvements.

“The structure of the Master Project is logical and organic, musicians today can no longer just be soloist virtuosi”

(Natan student, Classical Department)

References

AEC Learning Outcomes 2nd cycle: Click here.

Craenen, P. Artistic Research as an Integrative force. A critical look at the role of master’s research at Dutch conservatoires. In Forum+,2020 (27:1), 45-55

Mascolo, M. F. Beyond student-centered and teacher-centered pedagogy:Teaching and learning as guided participation. In Pedagogy and the Human Sciences, 2009 (1:1), 3-27.

Polifonia: Click here.

Royal Conservatoire The Hague. Master of Music Handbook. 2020.